(apart from the “living room” there are a number of other rooms (or rather pages))

I plan to “translate” my Japanese website, but have just begun. It will take some time. Please bear with me.

This page lists the following topics

My story

Master ….

Responsibility

Personal experience

Position in society

Hayama Life – a foreigners different views (to dedicated page) Please have a look there.

My Story

Originally, I “just” wanted to travel around the world …

My way to Japan

I was born and grew up in the small port town Kiel facing the Baltic sea. Maybe that is why I have in my life always lived somewhere near the sea. By now, however, it is no longer in Germany, but rather in the small town Hayama in Kanagawa prefecture (Japan) half way around the world. Hayama used to be nothing more than a little fishing town, until the Japanese emperor built a secondary residence here and Hayama turned slowly into a luxury resort. Something I cannot related to. Talking to elderly fishermen born and raised in this town just confirms how pitiful this “development” actually is. Why then did I chose to live here? This is a short and simple and at the same time long story.

During childhood it is certainly not uncommon, that the younger brother (me) imitates an elder brother. So, when my elder brother started practicing judo, I just had to do the same. About two years later he started aikido and again I had to follow in his steps. However, aikido suited me much better than judo and so I quit the latter, concentrating on my aikido practice. I am a little embarrassed by saying so, but I made rather good progress. In between I tried once or twice kendo, but this too was not really ‘my thing’. With karate just watching it was sufficient to convince me, that this is not for me.

Some years later, when I had become a “sensei” = trainer, I encountered through one of my aikido students tai chi chuan. At first that person simply showed me this form of ‘kung fu’, but soon I asked my student to teach me one of the representative patterns. Immediately I noticed, that this ‘sports’ fits my preferences perfectly. Through a number of events and short trials with different sports I learned to intuitively discern forms suiting me and those that do not, which ultimately led to me coming to Japan. The defining event as a TV program.

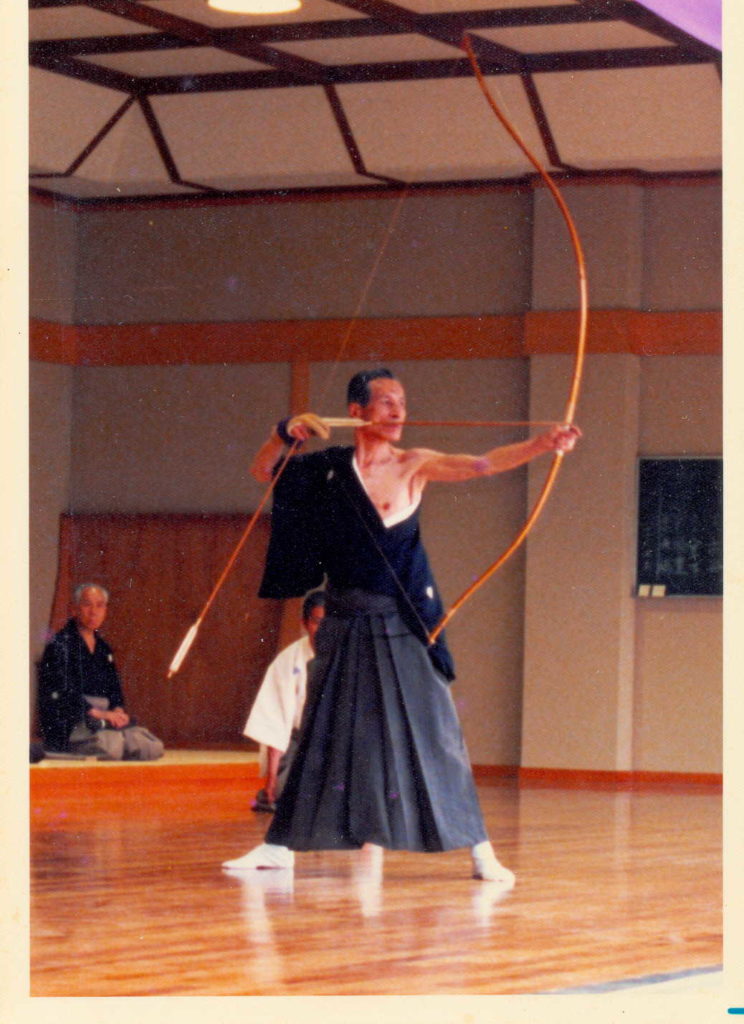

My kyudo teacher: Tanigawa sensei

At the age of 17 I was watching a documentary about marital arts on TV, covering just about everything, from judo, karate, aikido, kendo, tae kwon do, kung fu etc. … and the Japanese form of archry: kyudo. This form of martial arts uses a very long bow to show arrows towards a target at a distance of 28-meter. The European bow is much shorter than the Japanese one, but very powerful. That is why the posture and technique of pulling the bow differs. In a kyudo dojo (practice hall) the practitioners stand on a wooden floor and shoot their arrows across a lawn at the target(s) set in a bank of sand.

In the said TV program the bow master, however, stood on a lawn, slowly lifting, then equally slowly drawing the bow and finally, after a peculiar ‘waiting period’ released the arrow. Whether the arrow hit the target or not, was not shown in the TV program and the entire scene lasted just about 2 minutes.

But that was enough!

Just this little 2-minute TV clip triggered some sort of “spark” in my head. Like struck by lightning I immediately knew: This is it! I want – or more appropriately put I felt compelled – to learn kyudo!

Later I searched for a dojo where I can learn kyudo in Europe. At that time – before the event of internet, computer etc. – I found only two such dojos. One of which was located in Hamburg, about an hour by car from where I lived, and the other in Paris, 1,000 km away. Yet, (it should maybe called “naturally”) the teacher both dojos were Europeans. In the middle of puberty at the age of 17 I was obsessed with idealism and therefore becoming the pupil of a European teacher was totally out of the question. I wanted to learn from a “real” master, meaning a Japanese. The conclusion was obvious and beyond any doubt:

I have to go to Japan!

Five years later, after graduating from senior high school, completing the work in social service I had chosen to do as a conscientious objector and working temporarily in a company dealing with construction materials, I sold most of my possessions and with money I had saved during the preceding fives years and that earned on the job, I had about 10,000 Deutsche Mark (the German currency preceding the Euro) to convert into travelers check. With that I was all set to go. Naturally I ignored the objections of my parents and started my journey with a one-way ticket for the trans-Siberian railway. Hitchhiking took me up to Berlin, where I moved over to East-Berlin to catch a train via Poland to Moscow. From there a 10-day trip with the trans-Siberian railway took me to Vladivostok – the final stop of the line. From there it was a 2.5-day sea journey to Yokohama. The whole trip took about 2 weeks. In all the five years since I decided to to go Japan until leaving Germany at the age of 22 I never even once had any doubts about the decision itself or the feasibility of the whole plan!

Originally my plan was to travel to Japan and practice there kyudo for about 6 months. After that I intended to “wander” around South-East Asia, by myself a schoner (totally unrealistic!) to sail vial Australia to San Francisco and there meet a person supposed to be going there about one year after I left Germany. That was the plan.

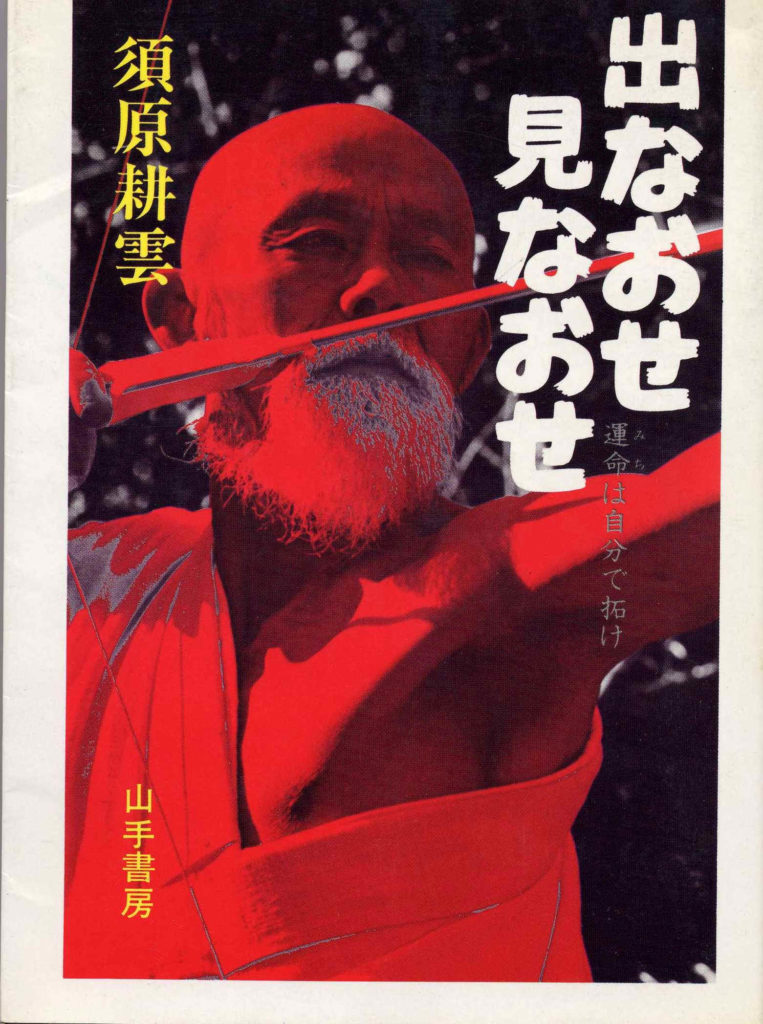

Once I was in Japan, I soon realized that finding a suitable dojo was much more difficult than expected. In particular the idealistic images and concepts I had acquired reading books in Germany proved to be mostly unrealistic. Yet, with the help of someone also practicing kyudo who interpreted for me, I was introduced to the Buddhist priest Koun Suhara in the Engaku temple in Kitakamakura, who was willing to give me some advice. With the help of many benefactors abbot Suhara had also set up a kyudo dojo within the precinct of the temple that fitted my dreams. Just being able to visit this priest in his home = temple with it typical Japanese interior impressed me immensely.

Below is a picture of the cover of a book Suhara sensei wrote. It reads “Denaose – Minaose” meaning something along the line “Start anew — Look again” (I have translated this book. See below).

Considering it my “mission” to repay my debt to Suhara  sensei I translated his autobiography and published it on 2024/4/11 on Amazon and Book2Read. Unfortunately the “conversion” made by those sites to render it readable on ebook readers had rather unappealing results. If interested, I can send you some better looking files (against a small fee).

sensei I translated his autobiography and published it on 2024/4/11 on Amazon and Book2Read. Unfortunately the “conversion” made by those sites to render it readable on ebook readers had rather unappealing results. If interested, I can send you some better looking files (against a small fee).

Naturally, I got a very clear answer from abbot Suhara too: “Unless you can communicate in Japanese, no teacher will be able/willing to teach you. You cannot expect white-haired elderly masters to learn English, not to speak of German, just to teach you. Therefore, go and study Japanese for 1-2 years and then come back.”

Being fascinated and stimulated by master Koun Suhara I decided to change the tourist visa I had at the time to a student visa and stay longer – period not set.

I don’t know the current regulations, but at that time you were required to leave the country and apply for a visa somewhere, anywhere, where there is a Japanese embassy. Since I have an acquaintance in Hongkong, that’s were I went. While waiting for my visa application to be granted, I started studying tai chi chuan under the tutelage of a teacher my friend had introduced me to. The formalities with the visa application however, ran into some trouble, resulting in an extension of my stay in HK to three months, rather than the expected three weeks. During that period I had to return once to Japan to obtain some missing paper, only to get the stamp in my passport back in HK.

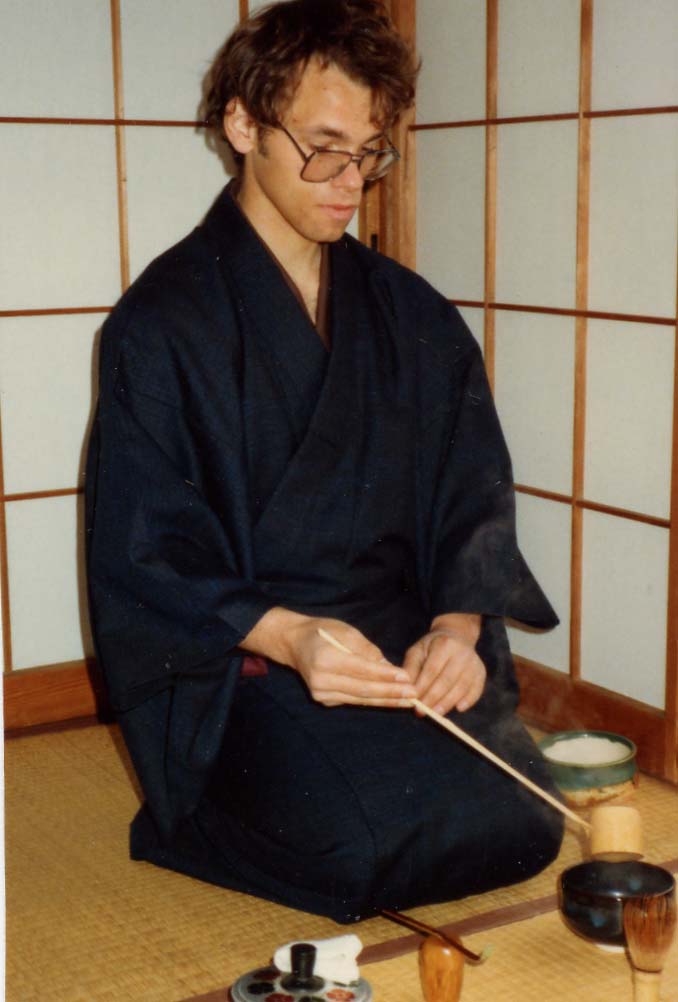

Tea ceremony practice

The following two years, however, were really fun. Several times a week I went to the dojo to practice kyudo (unfortunately not in the temple dojo mentioned above), practiced tea ceremony and every day climbed a little mountain behind my apartment to practice tai chi chuan on the mountain top over-viewing the Sagami bay with a beautiful view of Mt. Fuji on clear days. For me this was just delightful …

During that period I met a number of Japanese people, some of whom are still friends today, and “of course” my wife. The contact with Japanese people greatly helped with my Japanese studies – although there were/are a number o pitfalls usually not known to foreigners. For example, assuming that Japanese people (always) speak correct ‘standard Japanese’ was a big mistake. Naturally, I knew about slang, but from the people (mostly male) I had rather frequent contact with (a sort of motorcycle ‘gang’ in the sense of unusual motorcycle fans) I learned a number or expressions that are better avoided unless you know exactly what you are saying. At that time my wife was a student of German conversation. Then I did not yet know that there expressions are sometimes different for men and women. The female students in my German class were all rather elegant and noble, so that I presumed their Japanese being a refined form of the language. Young and enthusiastic I imitated their use of words in front of those motorcycle fans, embarrassing myself on more than one occasion.

Considering graduation from high school in Germany, completion of the social service work I chose instead of an obligatory period in the military to be a good timing for leaving the country. Since I did not study or learned a profession, it became necessary to think about how I am going make my living in the future. This was when my interest in oriental philosophy surfaced. By that I mean, learning shiatsu as a profession would allow me to combine work with my interest in oriental philosophy. Since there are sick people everywhere on the planet, I would be able to earn a stable income. Or so I thought.

The typical attitude of an inexperienced youngster. By now I learned, that things are not proceeding that smoothly. Apart from that, I decided after a while to ‘broaden my therapeutic horizon to include the study of acupuncture and moxibustion. After a 3-year education in a vocational school I obtained following a state examination my licenses for acupuncture, moxibustion (these are two different licenses in Japan) as well as shiatsu, anma and massage (the latter three are covered by one license). After passing this examination you are qualified to open your own clinic.

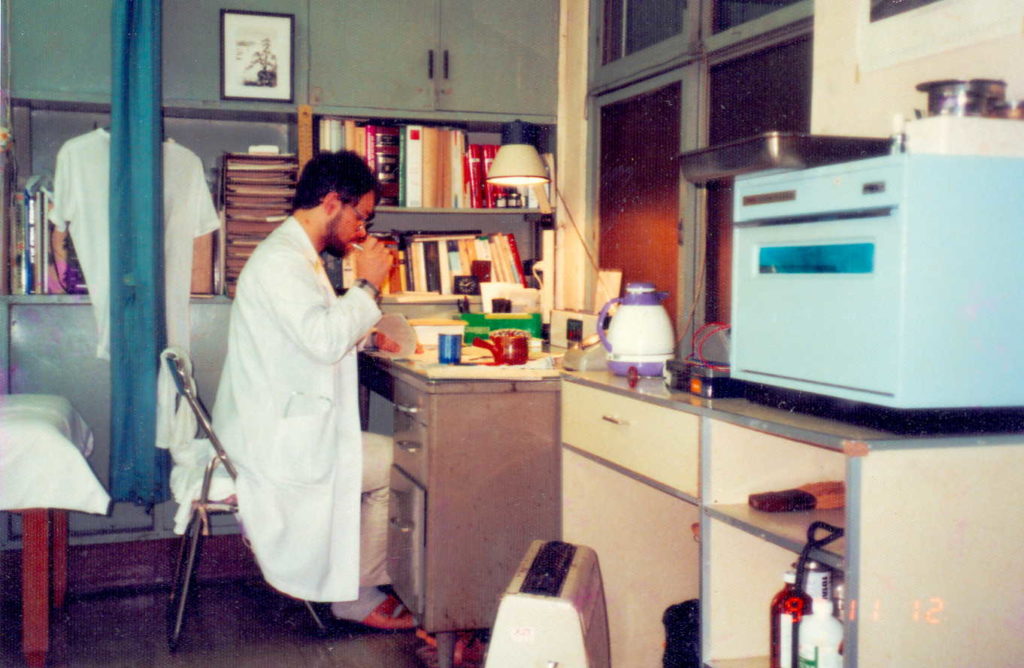

Yet, I was given the opportunity to gain on-site clinical experience by studying for a while, four years to be precise, in the ‘Department of Oriental Medical Research’ in the Tamagawa General Hospital in Tokyo. I was not an “employee” of the hospital, but one of the 15-16 acupuncturist who were (gracefully) permitted to work there. To get there in time I boarded the train every day at about 7 o’clock in the morning and came home by 10-11 at night. Six days a week. Naturally my other activities like kyudo, tea ceremony and other things had to be put on hold. However, in exchange for that sacrifice I gained the opportunities to study things in the hospital I would never had any place elsewhere. As a young German acupuncturist working in a Japanese hospital, not just observing the department one day, I believe I was a quite exotic presence there. While I did not / do not like being treated somewhat like a circus number, it permitted me some of the freedoms a clown has: I was the only person there who could ignore the notorious “factional infighting”. That gave me the chance to study a lot of things my fellow acupuncturists could not, like asking doctors from the “enemy camp” questions etc.

After working in the hospital for four years, during which we had three children, I started working as a freelance translator and as an acupuncturist making only house calls until I opened in 1995 my very small clinic in Hayama. This is where I still today, after 27 years, try to help my patients to the best of my abilities. Two years after the corona pandemic started there is practically no translation work left. Apart from having difficulties putting food on the table, this suits me in a sense just fine. I used to think translation is my ‘job’, the foundation of our livelihood, but treating people is my ‘vocation’, the thing I am supposed to do. Interestingly the German term for ‘profession’ is ‘Beruf’, which is derived from the term ‘Berufung’ = vocation often used in religious contexts. Put a little more modest it might be called ‘mission’. Since the children are by now all grown I MIGHT be able to pursue my vocation without starving to death. After all, THIS is what I like to do. Even though I not any sort of ‘expert’, just a third class craftsman.

Although I tried hard not to, I did ‘stick out’ in the acupuncture community in Japan. The reason? Quite simple: There are VERY few western (nobody would be surprised when a Chinese (= also foreigner!) opens an acupuncture clinic) foreigner runs his or her own acupuncture clinic in this country. Personally I know of only 4, me included, such places. Although I gave up tried to determine the exact number, I suspect there cannot more than maybe 10 Westerners running an acupuncture clinic.

This is how my plan for a 1-year trip around the world ended up in my remaining permanently in Japan. By now I already celebrated my “ruby wedding” with my Japanese wife and we have 4 grown children. I tried over the past 20 something years to provide what little assistance I can offer to people from “overseas” (that is a funny expression; since Japan is an island, EVERY other country is “overseas”) trying to learn or do something related to acupuncture in Japan. Unfortunately my social life is rather restricted and so are my “resources”. Yet, also based on personal experience, I somehow consider it my “mission” to help foreigners trying to learn something about Japanese acupuncture. In particular since Japanese practitioners are not really forthcoming in this area.

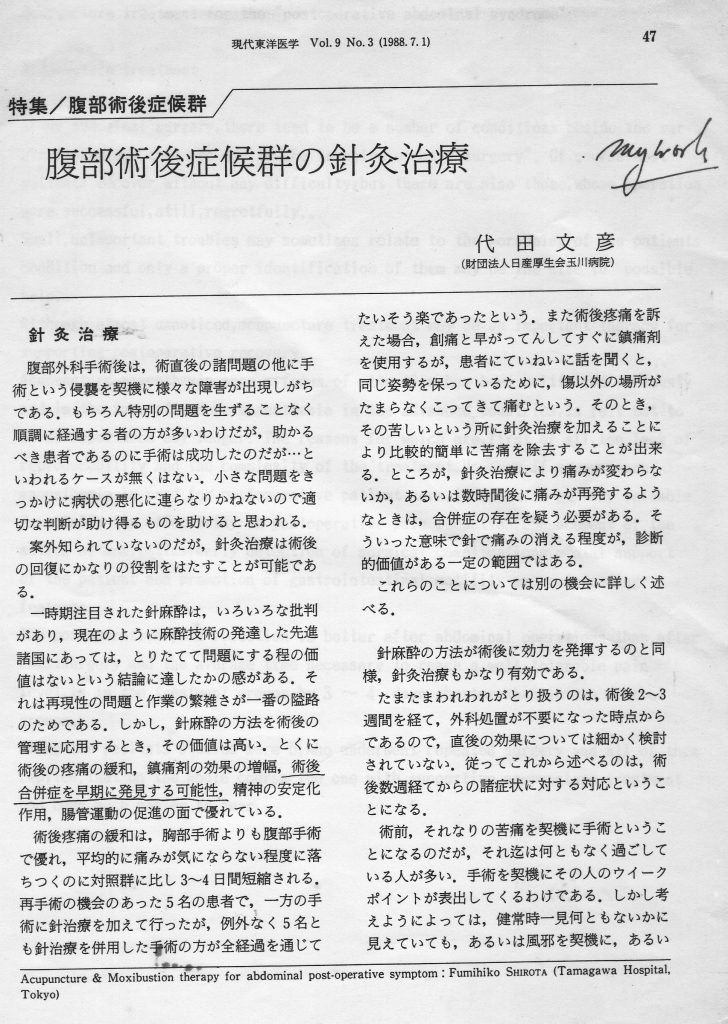

One of the studies I had an opportunity to conduct while working at Tamagawa hospital was the application of acupuncture for pain control after surgery. That work of mine has been published in a Japanese magazine and a German magazine. (Those articles can be downloaded from the download page.) After I presented Dr. Shirota with my paper, he congratulated me on the good work. A few years later I by accident discovered an article in a specialist journal with pratical the same wording, published under Dr. Shirota’s name. I definitely do not hold a grudge against Dr. Shirota, but it might have been nice, if he had told me.

Following requests from a number of patients, about 8 years ago I wrote my “life story” as an ebook (in Japanese; later I reworte it in German but did not write an English version yet) published here (and at several other locations):

https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/434933

Master …

Although I consider myself nothing more than a third class craftsman, people here continue to call me “sensei” – the Japanese word for master, teacher, etc.

I think, an acupuncturist is supposed to be a master = model for the local community, looking back on a 1,500-year tradition of good leader of the country = teacher or sensei, where the characters for sensei = 先生 can be interpreted as “one who lives as a model in front of the others”. THAT, however, is my personal interpretation. Most Japanese people interpret the word simply as one who has been born earlier that others. Yet, as such a sensei = master an/the acupuncturist should strive to contribute to the health of the community.

In my opinion the wisdom of oriental medicine should be intellectual property (and maybe also common sense) of the people and thus acupuncturist guide the community based on this treasure so that individuals can enjoy a more healthy life and society save some money otherwise spent on very expensive (and often useless/redundant treatments). Thereby the acupuncturist may help to achieve a healthier society.

Similar to the above mentioned word “sensei” there is a verb describing what a teacher does: “shidou” – meaning mostly “guiding”, instructing/teaching, leading the way. The term is made up of two characters: 1) finger and 2) leading. It is like an adult offering a hand to a child, which cannot grasp the whole hand, but only one finger and then follows this finger. The second character “leading” is composed of two parts: way/path and inch. Personally I interpret this term, i.e., the function of a teacher/master is showing deciples the right way, go one inch on it in the right direction and then let the deciple/student/patient etc. go on alone, while the teacher stays behind. That is MY interpretation and definitely not linguistically correct, but sometimes it helps with the explanation of the patient-therapist relationship.

Responsibility

The third basic concept: “Man is responsible for his (and other life forms) health (life).” Writing this kind of statements is likely to draw heavy criticism, but it is now necessary that the underlying truth is recognized once more. Patients are (mostly) not responsible for injuries, infections or inherited diseases, but physical discomfort or even disorder due to poor posture or other bad habits is not fate. Unless some efforts are made to remove the underlying cause for the disorder, acupuncture treatment too will likely have limited effects.

I consider treatments aiming at having patients commute instead of addressing the basic causes unethical.

Be an example yourself

An earnest acupuncturist first tries/experiences the kind of treatment s/he is going to administer to his/her patients. Acupuncturist treat themselves with acupuncture moxibustion, practice exercises and other things they might suggest to their patients. I believe that is the way to implement the above mentioned concept of “sensei” = living before/in front of others.

And if there are treatment forms/techniques one would prefer NOT to have done on oneself, then they should also not administered to others .. unless it deemed really necessary.

That is the treatment style of past great therapist – and to me this sounds very convincing.

Personally I do not like the “needle sensation” so much praised by the Chinese. Many of my patients do not like it either. So, if not necessary, I practice acupuncture WITHOUT that needle sensation and – if I may dare say so – doing not too bad with this style.

About 19 years ago I had to undergo surgery for my right shoulder after a bicycle accident. That experience taught me first hand about how patients feel after surgery. Recalling how I counseled the patients I treated for postsurgical pain in the hospital 30 years ago, I can only feel like begging for forgiveness for my lack of knowledge and understanding. The same holds true for exercise. Advising the patients to exercise but not doing it yourself is NOT very convincing.

A number of years ago I had another bicycle accident. THAT taught me the absolute necessity for a helmet when riding a bike! I wrote a sort of blog entry about this, but the English translation is not yet finished.

Social status …

My personal opinion and views on everyday things may not be ‘normal’ and sometimes outright contradict common sense. For that I am often criticized. On of the points where my preference differ somewhat from the ‘norm’ is clothing.

Here in Japan patients are in recent years not simply called ‘patient’ but rather ‘patient + honorific’ (the honorific is a term/concept not used in English or other European languages, unless you revert to a language usage a few centuries old). Which then mean (again mostly here in Japan) that the practitioner is supposed to ‘honor’ the patient by wearing a suit, necktie and on top of it a white coat (the latter often being called ‘lab coat’, something I detest even more). However, I am not a scholar and definitely not a member of the wealthy upper class. I am just an ordinary physical laborer – a third class craftsman at best.

So, I think, I should dress accordingly. Not in some fancy high-priced brand clothes, but ordinary working pants, shirt etc. As long as the clothes are not dirty, that should do just fine. Befitting my ‘social status’. Wearing a suit would not change the efforts I make during the treatment of my patients – or improve my skills for that matter. So, please let me be me. In the hope you will bear with me.

Here is a blog (mostly in Japanese!) about those somewhat unorthodox opinions of mine. You are nevertheless welcome to take a look: → ドイツ人鍼灸師の意見=異見

Voices — on this page you find some comments / reviews by people who visited me. Again mostly in Japanese. There is also the possibility to LEAVE a comment. That is, if I got the setting right (still trying to figure out, how these things work) …

List of hashtags I added. This is a test.

鍼 #針 #鍼灸 #鍼灸院 #東洋医学 #伝統 #職人 #葉山 #逗子 #おきゅう #肩凝り #眼精疲労 全身疲労 #難病 #履歴 #歴史 #自伝 #お話 #ドイツ人 #トーマス #トーマス鍼灸院 #鍼灸師 #英語 #ドイツ語 #用語集 #翻訳 #通訳 #低所得者 #丁寧な説明 #書籍 #acupuncture #moxibustion #clinic #English #German #Hayama #Zushi #StiffShoulders #LowBackPain #SystemicDiseases #LowIncome #alternativetherapy #holistic #interview #personlized #books #translation #interpretation #glossary #oriental #medicine #books #recommend #therapy

![]()